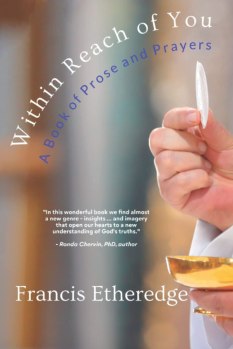

Within Reach of You: A Book of Prose and Prayers by Francis Etheredge (St. Louis, MO: En Route Books and Media, 2021, 260 pp.)

Within Reach of You: A Book of Prose and Prayers by Francis Etheredge (St. Louis, MO: En Route Books and Media, 2021, 260 pp.)

Reviewed by Christine Sunderland

When do prayers become poems and poems become prayers? When they are addressed to God who is present and listening. In Francis Etheredge’s third volume of his trilogy of prose, poetry, and prayer, he turns prayer into poetry and poetry into prayer, shining light onto words as pathways into the presence of God. As in the previous two volumes, he introduces the prayers with meditations.

In Mr. Etheredge’s first volume in this trilogy, The Prayerful Kiss, he writes of his personal journey from sinner to saved, and in this search for meaning and forgiveness, somewhat like the prodigal son, he meets God (or God meets him?) and is reborn, now seeing all life as sacred. In the second collection in the trilogy, Honest Rust and Gold, he journeys deeper into the action of God’s grace upon us and within us, recreating us through the sacraments of the Church as we are baptized in Christ’s love.

In this third volume, Within Reach of You: A Book of Prose and Prayers, prayer becomes poetic, as it weaves the eternal into the mortal, life into death. Prayer becomes the true desire of poetry, to reach for God and touch the holy, reaching for words that describe the indescribable, that explain the unexplainable, through metaphor and image. For we live within the created order, a sacred but fallen world, just as we are sacred but fallen. We must use words to touch the sacred, to sing of glory to our fallen world.

Thus, we reach for Christ in these prayers, entering a holy space. As seen in the cover image, we reach for the Host, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, offered to us, within our reach. The title is two-way, perhaps: Christ is within our reach, and we are within the reach of Christ, through prayer, through sacraments, through the Church. This intimate touch is personal, for, like Moses, we stand before a burning bush, one that does not burn up or burn us, but gives us light to see, enlightening us, loving us. In this light, we see our way forward:

“What is Prayer? Prayer is immediate because God is present…. Prayer is personal – because it arises out of each person’s life; and prayer is communal because we pray with all who pray for all who need prayers… we are speaking to one who listens; and, whether we use words or not there is prayer in the intention to pray. Prayer is challenging because it may not be answered as we ask…. Prayer is for the smallest need and the greatest common good. Prayer excludes no one and includes everyone… prayer makes it possible for us to accompany both the living and the dead into the presence of God.” (xxviii-xxix) (italics mine)

And so the trilogy moves from a personal pilgrimage into faith, to faithful participation in Christ’s Church, and lastly to praying for the world, past and present and future, the living and the dead, the communion of mankind, as we can only pray when we are in that space in reach of God.

Prayer, we see, is rooted in our daily life, in our family life, in our parish life, in our community life, and in the suffering life of the world. Prayer gives “flesh to the daily, ordinary or extraordinary situations out of which prayer arises” (6). In this sense we pray without ceasing, placing us always in God’s presence: “He is present to all that we do” (31). He works daily miracles in our lives. We need only reach for him, watching and praying, and, in a sense, allow him the space to work his will in us, “making possible the impossible” (34). In Mr. Etheredge’s prayer-poem “Pilgrimage,” he prays, “You know how your word passed through my life to the core/ Of what I wanted: ‘I come to give you life and life to the full’” (cf. Jn 10: 10) (35). Indeed, we are full, fulfilled, fulsome when we are in the presence of God.

Rooted in the real world, prayer can be simply “blessing God for the splashes of life” (41) that we see all around us. It is true, I have found, that simply giving thanks opens that space for God to reach us. And there are always reasons to give thanks – for life, for breath, for each day given, for my cat (!), for my family, for… Christ himself amidst the splashing life all around me. Indeed, I give thanks for being in reach of God, he in us and we in him.

Mr. Etheredge soon moves beyond the natural world rooted in family and the earthy Earth, to the universe. We see how faith and reason blend, supporting one another, reflecting the creation and the Creator: “Who knows how the universe goes, whirling and twirling and/ Curving through elliptical twists and turns, burning here and/ Freezing there, gaseous and solid, but solidly dynamic and moving,/ Cascading and still, still as staying in one place while moving… ” (51)

With these profound echoes of T. S. Eliot, we journey into the creative Word of God reaching and touching us, in time, in Scripture, in history, in people in our midst. All these Words of God speak to those who witness with their words, witness to the manifold works of God in our world and in our hearts:

“Take us as we are, where we are, with whom we are and open our

Lives to your word, mingling your word with our lives, like the

Mingling of water and the Holy Spirit through which you come to

Dwell in us, opening up the wells of salvation sunk in the union

Of our Savior, Jesus Christ, with each one of us, when the word

Became flesh (Jn 1: 14) and entered the whole of human history

Taking my history and yours and making of it the history of salvation (56).” (italics mine)

In this precious collection of prayer-poems we pray for our wayward culture, today’s culture of death. It is a culture that must be baptized by the Holy Spirit, to assert good over evil, truth over falsehood, love over hatred. And so, we pray, come Holy Spirit, bathe our culture with Christ’s love and all life, from conception to grave. We pray that we humans humanize our race by embracing our beginnings at conception, cherishing our unborn: “There must be in the heart of all a desire to improve the life of the nation; indeed, to be a part of progressing the welfare of all. For, without peace, who can build? Without truth, who knows what is happening and what needs to be done? Without love, what good will there be for any of us?” (218) (italics mine)

In prayer, God grows within us: “The presence of God, then, while always and everywhere true, is at the same time like a seed-to-be-perceived and, therefore, grows through prayer, the life of the Church and our enfolded, unfolded living of it. So, while our weakness may increase, it only increases to magnify the power of the Lord and our hope in Him” (251). (italics mine)

And so much more…

Within Reach of You places you and me in God’s presence. For when poetry becomes prayer, we are given a great gift: not only the vision of God, but a personal God, a present God. Our beginnings and endings and beginnings again as we enter eternal life are found and founded in the love of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, in this world without end. Amen.

Francis Etheredge is a Catholic theologian, writer, and speaker, living in England. He is married, with eight children, plus three in heaven. Mr. Etheredge holds a BA Div, an MA in Catholic Theology, a PGC in Biblical Studies, a PGC in Higher Education, and an MA in Marriage and Family. He is author of 11 books on Amazon:

Visit Francis Etheredge at Linked-In for book news and blog posts.

Christine Sunderland serves as Managing Editor for American Church Union Publishing. She is the author of seven award-winning novels about faith and family, freedom of speech and religion, and the importance of history and human dignity. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband and an incredible white longhair cat named Angel.

Christ is risen, he is risen indeed!

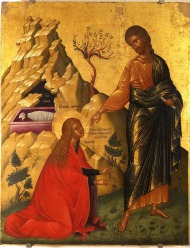

Christ is risen, he is risen indeed! And so today, after re-enacting the drama of Holy Week – Maundy Thursday and the institution of the Holy Eucharist at the Last Supper, the Good Friday arrest, trial, and crucifixion of Our Lord on a hill outside the gates, the deathly silence of Holy Saturday and the evening lighting of the paschal candle, the world waiting for rebirth, for resurrection – we find Mary Magdalene discovering the empty tomb and meeting the resurrected Lord of Life.

And so today, after re-enacting the drama of Holy Week – Maundy Thursday and the institution of the Holy Eucharist at the Last Supper, the Good Friday arrest, trial, and crucifixion of Our Lord on a hill outside the gates, the deathly silence of Holy Saturday and the evening lighting of the paschal candle, the world waiting for rebirth, for resurrection – we find Mary Magdalene discovering the empty tomb and meeting the resurrected Lord of Life. Easter holds hope within it. Dawn breaks on an early spring morning, and we assemble in church to sing well-known Easter hymns, flower a white cross, drape a white mantel over the now visible crucifix above the altar. Gone are the purple shrouds of Passiontide, those weeks leading to this moment of joy. We too bare our souls, removing the shrouds of death and despair, as we don the garments of life and joy.

Easter holds hope within it. Dawn breaks on an early spring morning, and we assemble in church to sing well-known Easter hymns, flower a white cross, drape a white mantel over the now visible crucifix above the altar. Gone are the purple shrouds of Passiontide, those weeks leading to this moment of joy. We too bare our souls, removing the shrouds of death and despair, as we don the garments of life and joy. Perhaps it was the gold vestments against the crimson carpet at St. Peter’s Pro-Cathedral in Oakland that made the Mass of the Holy Ghost one of such deep beauty. Certainly the chanting from the choir loft behind us enhanced this sense of heaven and earth, the light angelic descants swirling over and around our mortal flesh in the weighty oak pews. It was both solemn and joyous, for we were thankful for our archbishop’s careful care over the last year and were happy to witness the installation of our new bishop.

Perhaps it was the gold vestments against the crimson carpet at St. Peter’s Pro-Cathedral in Oakland that made the Mass of the Holy Ghost one of such deep beauty. Certainly the chanting from the choir loft behind us enhanced this sense of heaven and earth, the light angelic descants swirling over and around our mortal flesh in the weighty oak pews. It was both solemn and joyous, for we were thankful for our archbishop’s careful care over the last year and were happy to witness the installation of our new bishop. It’s been raining here in northern California and our happy earth drinks in the spring drenching, this gift from the heavens. Perhaps our rolling greens will not turn to golden browns quite yet.

It’s been raining here in northern California and our happy earth drinks in the spring drenching, this gift from the heavens. Perhaps our rolling greens will not turn to golden browns quite yet. Today is called Good Shepherd Sunday. I have a beloved icon that shows Christ in red-and-blue robes carrying a lamb over His shoulders. A wooden crossbeam stretches behind Him. Christ is the Good Shepherd who loves His sheep. He knows them and they know Him. The lamb He carries is like the lamb carried into the temple for sacrifice. We know, of course, that Christ is the sacrificial lamb. He replaces the lamb once sacrificed. For love of us.

Today is called Good Shepherd Sunday. I have a beloved icon that shows Christ in red-and-blue robes carrying a lamb over His shoulders. A wooden crossbeam stretches behind Him. Christ is the Good Shepherd who loves His sheep. He knows them and they know Him. The lamb He carries is like the lamb carried into the temple for sacrifice. We know, of course, that Christ is the sacrificial lamb. He replaces the lamb once sacrificed. For love of us. It is a rich and glorious season, this time of Eastertide.

It is a rich and glorious season, this time of Eastertide.

It’s been a week of words, words, words, and more words.

It’s been a week of words, words, words, and more words.